We began this lesson with the Great Storm that hit Galveston in 1900. Since then, there have been many notable storms — some impressive because of their strength and some because of their destruction.

1. Research destructive storms and create a table of devastation for five of them, using the information you find. Here are some places with information to help you choose which storms to use and facts about their destruction:

2. As you may have read, it isn’t always the wind and rain of the hurricane that causes the most damage. Storm surge and fire also cause destruction. Damage can also be impacted by the quality of construction and other factors. Read about storm surges and then answer this question: What can create dynamic of weaker storms causing more devastation than stronger storms?

When your hurricane hits land, how much damage and what kind of damage will it do? (Be sure that the damage matches the category of storm you chose.)

Now imagine that you are a journalist who writes about extreme weather. Write a newspaper article about your hurricane; read an example here. Make sure to include a visual image (a map, a chart, a picture, etc.). Follow the rubric below to make sure that your article is effective.

You have read (and written) about hurricanes. Now it is time to do some research of your own. With your parents’ permission, interview two people you know about the most dramatic weather incident they have ever experienced. Make a list of questions to ask them. Possible questions include subjects such as how old they were, why they remember this particular incident, what were the reactions of people around them, and so on. When you have interviewed both of them, write about the incidents below, comparing and contrasting the experiences. Be sure to write at least one way in which they were similar and one way in which they were different.

Read the following excerpt from Joseph Conrad’s story, Typhoon.

Nobody — not even Captain MacWhirr, who alone on deck had caught sight of a white line of foam coming on at such a height that he couldn’t believe his eyes — nobody was to know the steepness of that sea and the awful depth of the hollow the hurricane had scooped out behind the running wall of water.

It raced to meet the ship, and, with a pause, as of girding the loins, the Nan-Shan lifted her bows and leaped. The flames in all the lamps sank, darkening the engine-room. One went out. With a tearing crash and a swirling, raving tumult, tons of water fell upon the deck, as though the ship had darted under the foot of a cataract [a cataract is a large waterfall].

Down there they looked at each other, stunned.

"Swept from end to end, by God!" bawled Jukes.

She dipped into the hollow straight down, as if going over the edge of the world. The engine-room toppled forward menacingly, like the inside of a tower nodding in an earthquake. An awful racket, of iron things falling, came from the stokehold. She hung on this appalling slant long enough for Beale to drop on his hands and knees and begin to crawl as if he meant to fly on all fours out of the engine-room, and for Mr. Rout to turn his head slowly, rigid, cavernous, with the lower jaw dropping. Jukes had shut his eyes, and his face in a moment became hopelessly blank and gentle, like the face of a blind man.

At last she rose slowly, staggering, as if she had to lift a mountain with her bows.

Mr. Rout shut his mouth; Jukes blinked; and little Beale stood up hastily.

"Another one like this, and that’s the last of her," cried the chief.

He and Jukes looked at each other, and the same thought came into their heads. The Captain! Everything must have been swept away.

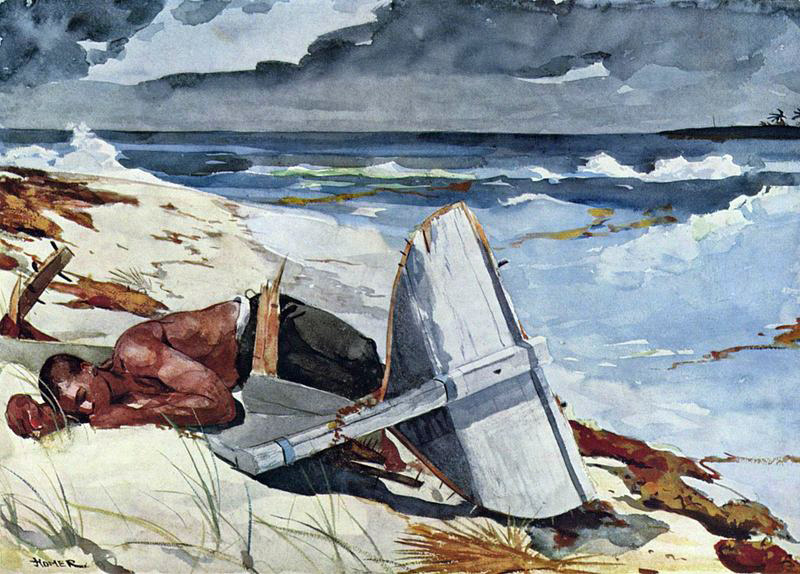

Look at this painting by Winslow Homer called After the Hurricane (1899).

What in the picture hints at the power of the storm that has passed? Give at least three details. What in the picture hints at the power of the storm that has passed? Give at least three details. Think of another name for the painting.

Read about the Hurricane Hunters! Even though most people try to avoid hurricanes, some brave people actually fly into them — on purpose!

Hurricanes in the movies!

Books!

Caution! Grown-up books ahead!

Discover the hurricane/El Nino connection!

Want to more about weather? Check out the World Weather Information Service.

Blog! This site calls itself a "blog," but really it's just got great information on hurricanes, and the graphics are really clear. This link takes you to the parts of a hurricane, but there are many useful pages to explore: accuweather.com/en/weather-blogs/hurricanefacts/what-are-the-parts-of-a-hurric/31027.

National Hurricane Center in the news! Read articles that have appeared in The New York Times about the National Hurricane Center.

Go straight to the source! Read a first-hand account of Galveston Hurricane published in The New York Times in 1900.

Lesson 2: Definitions and descriptions

Lesson 3: Analyzing the effects of a hurricane

| 1. 5 | 2. Yes | 3. Flying or falling debris | 4. Rubric for questionnaire: See below: |

Lesson 4: Tracking and comparing hurricanes

This section should be assessed holistically, with the student creating neat charts that clearly show the paths of the storms. Their answer to question 9 should reflect thoughtfulness and an understanding of the information gleaned from the information provided. This section could appropriately reflect 5-10% of the student's grade on the lesson plan.

Lesson 5: The name game

Lesson 6: Historic storms

Lesson 7: Create your own hurricane

Lesson 8: Investigation — unassessed

Lesson 9: Literary connection

This section should be assessed holistically, with answers reflecting thoughtful response and an understanding of the literary element of simile. This section could appropriately reflect 2-3% of the overall grade on the lesson plan.

Lesson 10: Fine arts connection — unassessed

Answer to question about hurricane names:

The letters q, u, x, y and z are not used.

This series of lessons was designed to meet the needs of gifted children for extension beyond the standard curriculum with the greatest ease of use for the educator. The lessons may be given to the students for individual self-guided work, or they may be taught in a classroom or a home-school setting. Assessment strategies and rubrics are included at the end of each section. The rubrics often include a column for "scholar points," which are invitations for students to extend their efforts beyond that which is required, incorporating creativity or higher level technical skills.